Product Development

Editors' Commentary: On the shoulders of hoarders

Why NEJM's data sharing editorial fails science, medicine and patients

The half-hearted "clarification" to a Jan. 21 editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine did nothing to address the journal's elitist and regressive attitude to data sharing and transparency in science. The values embodied and solutions proposed in the original editorial, which launched a Twitterstorm of indignation, would serve the community badly and would do more to hold back science than accelerate it, which is unquestionably bad for the patients whose collective sacrifice NEJM says must be honored.

In a nutshell, NEJM Editor-in-Chief Jeffrey Drazen and Deputy Editor Dan Longo argue that clinical researchers should not be required to disclose their assumptions to data scientists or other researchers who want to build on the original research. Moreover, the NEJM editors cite arguments that these follow-on researchers are "parasites" who accumulate personal and financial gain on the backs of the original data gatherers.

Frankly, it's too bad some researchers believe they receive no benefit from making their data freely available after they spent years gathering it, while others sweep in and reap the rewards at no cost. But salving their feelings is no reason to throw out the bedrock principles of the scientific method.

It's certainly not a rationale for journals like NEJM to endorse self-pity and erect barriers so that data-hoarders can hinder the free flow of information needed to accelerate scientific and clinical inquiry. Instead, they, together with the wider community, should find ways to incentivize even greater data transparency.

Drazen and Longo began their editorial by trivializing the efforts of data scientists under a thin veneer of apparent support for data sharing.

"What could be better than having high-quality information carefully reexamined for the possibility that new nuggets of useful data are lying there, previously unseen?" they wrote. "The potential for leveraging existing results for even more benefit pays appropriate increased tribute to the patients who put themselves at risk to generate the data. The moral imperative to honor their collective sacrifice is the trump card that takes this trick."

They then launched into a series of "concerns" about whether and how those data could be used, with an astonishing disregard for the very principles of scientific inquiry.

Their first concern: "That someone not involved in the generation and collection of the data may not understand the choices made in defining the parameters."

That attitude is completely unacceptable in scientific reporting. All data choices must be explained. To do otherwise leads to irreproducible data in preclinical research, and -- worse -- data in clinical research that doesn't parlay into expected results in medical practice. If you can't understand how heterogeneous a study population was, you can't evaluate its relevance in any population, and its usefulness is limited. The more detail you have, the more useful the data.

The answer is not to hold back from comparing independent studies but to require more detail, to allow the most meaningful data to be compared.

The second concern -- that "the system will be taken over by what some researchers have characterized as 'research parasites'" -- is ridiculous at best and at worst hypocritical and antithetical to science.

The NEJM editors defined this class of researchers as "people who had nothing to do with the design and execution of the study but use another group's data for their own ends, possibly stealing from the research productivity planned by the data gatherers, or even use the data to try to disprove what the original investigators had posited."

The objection to "stealing from research productivity planned by data gatherers" wouldn't stand up in a kindergarten schoolyard. You can't call dibs on all sandcastles you plan to build just because you built one today. Tomorrow your neighbor can take a better bucket and build a bigger one that lasts longer -- right next to yours. And she can write about it.

As for "using data to disprove what the original investigators had posited," critically evaluating data is exactly what scientists are supposed to do. We can't begin to understand what the objection is here.

After voicing these "concerns," the NEJM editors proposed solutions to enable data sharing that range from nonsense to inimical.

First, they suggest data scientists meet a new hurdle: "Start with a novel idea, one that is not an obvious extension of the reported work."

This is nonsense. The whole foundation of science is that it builds on published work.

More importantly, "novelty" and "lack of obviousness" are standards for patents, not publications. This kind of thinking disincentivizes swaths of research often thought of as incremental, but that form the crucial building blocks for moving from idea to product.

Is it novel to characterize a gene in a mouse that was first found in a rat? Today, that won't get you a big publication, but it's very useful information if you're trying to build a mouse model involving that gene.

And how far would clinical data sharing initiatives like the Project Data Sphere LLC consortium and Critical Path Institute's Coalition Against Major Diseases get in their quests if researchers accessing the data have to avoid "obvious extensions" of prior work? Not far.

Those initiatives were set up to mine comparator arm data to improve clinical trial designs and better understand variables like patient risk factors. "Novelty" is not their raison d'etre. But the work has as much potential to advance clinical science as any "novel" discovery.

The second and third proposals are to "identify potential collaborators whose collected data may be useful in assessing the hypothesis and propose a collaboration," and then "work together to test the new hypothesis."

That sounds very nice, but really just reinforces data-hoarding. If the authors don't want to collaborate -- or if you can't get a response from them -- should you just drop the idea?

Whom does it serve if you can't form a collaboration? Maybe the authors, but no one else.

The NEJM idea also assumes equal access around the globe to all researchers. Imagine a small group in a lesser known university or developing world country has a great idea stemming from a paper published by a top medical school or company: Does it just hand the idea over to the original paper's authors and ask for a collaboration? What protection does the group have over its idea?

Finally, NEJM entreats collaborators to "report the new findings with relevant coauthorship to acknowledge both the group that proposed the new idea and the investigative group that accrued the data that allowed it to be tested."

This gets at integrity in reporting. There are already regulations and etiquette on acknowledging sources of data and material. As to acknowledging whose idea it is -- that's a matter of personal integrity. One hopes that people do it. Often they don't. But short of the courts, there's always Twitter.

Whether or not it was the heated Twitter response that prompted a second missive from Drazen on Jan. 25, his "clarification" of the journal's stand on data sharing did not retreat from or modify one word in the original piece. Rather, he put the blame for the more disparaging remarks on unidentified clinical trialists around the world.

"To make data sharing successful, it is important to acknowledge and air those concerns," he wrote, and then doubled down on his rigid recommendations.

Legitimizing those concerns and recommending restrictive policies to mollify them moves us backward.

Finally, we'd remind the NEJM editors that almost all studies benefit from some level of funding from the public purse. That's a factor that sharing-shy scientists -- and the journals that publish their work, and charge others to read it -- need to acknowledge in their protectionist approach to hoarding information.

This article originally appeared in the Jan. 28 issue of BioCentury Innovations. The full table of contents for the issue can be seen on page 12. To learn how to receive a free trial, click here.

COMPANIES AND INSTITUTIONS Mentioned

Critical Path Institute, Tucson, Ariz.

Project Data Sphere LLC, Cary, N.C.

References

Drazen, J. "Data sharing and the Journal." New England Journal of Medicine (2016)

Longo, D. and Drazen, J. "Data sharing." New England Journal of Medicine (2016)

Figures

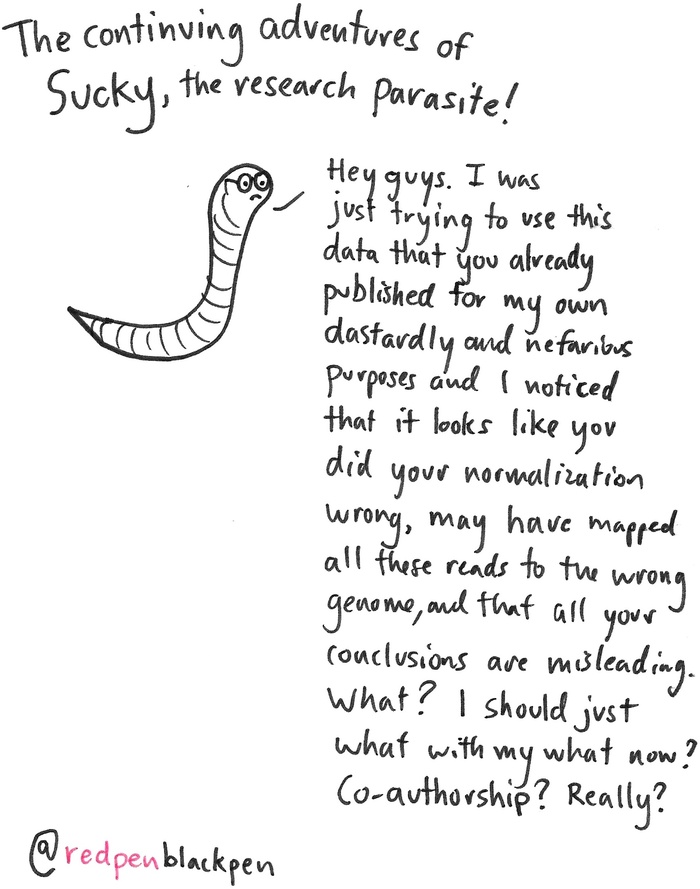

The continuing adventures of Sucky

Reproduced with permission from RedPen/BlackPen

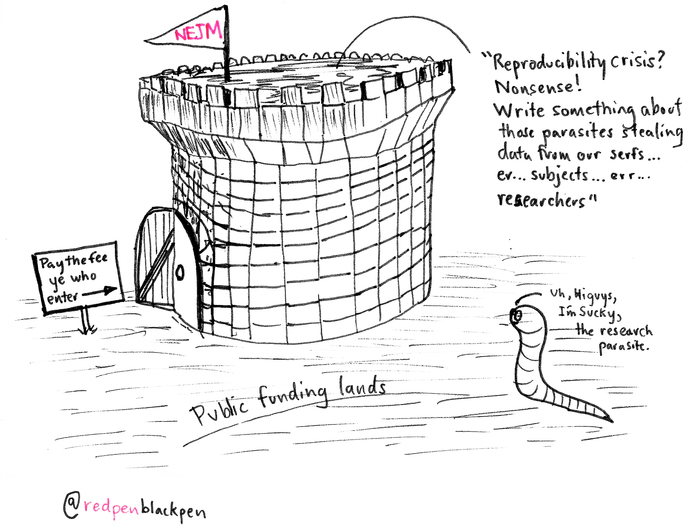

Sucky at the Castle Gate

Reproduced with permission from RedPen/BlackPen