Regulation

Don't skip DMD patients

Why FDA should grant accelerated approval to eteplirsen for DMD

The skimpy NDA for eteplirsen to treat Duchenne muscular dystrophy has FDA wedged between the rock of inconclusive data and the hard place of a well-informed patient community that understands the limitations of the data and still demands access to the compound. There are very good arguments for rejecting eteplirsen, but they are outweighed by the possibility that the compound might help and is very unlikely to harm boys who have no other hope.

In the interest of patients, FDA should grant accelerated approval to eteplirsen for DMD that is amenable to exon 51 skipping. The agency should couple the approval with stringent requirements for Sarepta Therapeutics Inc. to rigorously confirm clinical efficacy, as well as an unambiguous understanding that approval will be withdrawn if efficacy is not confirmed.

At the eteplirsen advisory committee meeting on April 25, Janet Woodcock, director of FDA's Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), was correct to highlight the impact of regulatory decisions on patients, and the imperative to give patients a greater say in how the agency applies its standards.

"Much of the effort in evaluating a drug development program goes into avoiding a specific mistake, that is, erroneously approving a drug that is not effective. There often is little consideration of another error, which is failing to approve a drug that actually works," she noted. "In devastating diseases, the consequences of this mistake can be extreme. But most of these consequences are borne by patients, who traditionally have little say in how the standards are implemented."

Sarepta's data for eteplirsen do not meet FDA's typical standards for either standard or accelerated approval. But DMD parents and patients are not typical, either, and their judgment should be brought to bear on the agency's decision.

The DMD community understands the data. Parents and patients have assessed the potential benefits and risks and have determined that uncertainty about eteplirsen's efficacy is not only acceptable, but preferable to the certainty that untreated DMD will cause a progressive loss of function and early death.

The decision is made easier by the apparent safety of eteplirsen.

Importantly, the availability of eteplirsen would not block more effective therapies from entering the clinic or reaching the market.

Moreover, granting accelerated approval to eteplirsen would neither represent FDA caving in to the emotional demands of patients, nor set a precedent for approving therapies that are more likely to harm than help patients.

Instead, it would set a positive precedent for the agency letting patients determine what level of risk and uncertainty is acceptable based on their experience of living with disease.

No favors

Sarepta hurt the case for eteplirsen and patients' chance for access by ignoring FDA's advice to conduct a placebo-controlled trial. Sarepta also left patients and investors in the dark about the compound's regulatory status, prompting FDA to take the unusual step of publicly refuting the company's characterization of its communications with the agency.

The company's choices mean it is not possible to rule out the chance that efficacy signals in the company's 12-person, historically controlled trial were the result of natural variation in progression, or of unwitting bias in study conduct.

The advisory committee was split on whether Sarepta's data on a surrogate marker for efficacy is predictive of benefit for patients. While seven members voted that Sarepta has not provided substantial evidence that eteplirsen induces dystrophin expression "to a level that is reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit," six members said the dystrophin expression data are likely to predict clinical benefit.

The data persuaded 36 scientists and physicians -- not just families overcome by tragedy -- that the compound has some clinical effect on DMD. In a February letter to Billy Dunn, director of the Division of Neurology Products, the researchers supported the choice of external controls used in Sarepta's study and said the improvement on six-minute walk distance (6MWD) relative to control was clinically significant.

The researchers and physicians also acknowledged that the only remedy for uncertainty about eteplirsen's effect is more study, and that it would be difficult to conduct placebo-controlled trials.

"We suggest that the most scientifically robust way forward and the most ethical choice for the Duchenne community is in the context of an accelerated approval followed by a confirmatory trial," they wrote.

We agree.

It is likely that approval would make it impossible to conduct placebo-controlled trials in the U.S. of future DMD treatments for the subpopulation indicated on an eteplirsen label. But it isn't clear this would be problematic. If the critics are correct and eteplirsen turns out to have no clinical efficacy, an eteplirsen arm in a comparative trial would in essence be a placebo arm.

On the other hand, if eteplirsen does have some efficacy, it would not be ethical to require patients with a progressive disease to forgo effective treatment.

FDA, Sarepta and the DMD community should work together to define a confirmatory trial that is large enough and appropriately designed to answer whether eteplirsen's apparent efficacy is real.

Not a precedent

Arguments that accelerated approval of eteplirsen would set a precedent for FDA caving in to emotional demands from patients have little merit.

Like the AIDS advocates who changed the way drugs are developed and regulated, the DMD community is demonstrating that emotional responses are not necessarily irrational. It is irrational to expect parents to be dispassionate about DMD.

It also would be irrational to fear that granting accelerated approval to eteplirsen would prevent patients and parents from seeking access to clinical trials of other, potentially more effective therapies -- two excellent reasons FDA usually does not and should not allow market access when evidence of efficacy is sketchy.

Mothers who are pushing for eteplirsen's approval know it isn't a miracle cure, and its approval wouldn't slow their efforts to find effective treatments or cures.

The parents of Duchenne patients persuaded Congress to invest hundreds of millions of dollars in DMD research and invested their own money in companies that are trying to turn that research into therapies. They facilitated the genetic testing, natural history studies and recruitment that made clinical trials possible, and they wrote draft guidance that served as the basis for FDA's evaluation of eteplirsen and other potential therapies.

These parents also have helped design, fund and conduct formal patient preference studies that demonstrate a deep understanding of risks -- and a clear and rational point of view about the trade-offs between risks and benefits of potential treatments.

In this case, the product appears to pose little risk. According to FDA reviewers, "No safety signal of significant concern has been identified for eteplirsen, although the clinical safety database for eteplirsen is small."

The database includes 114 patients in total. Twelve were exposed to eteplirsen for more than three years. Only 36 patients were exposed for 24 weeks or longer.

Another possible objection is that accelerated approval of eteplirsen, which would confer Orphan Drug status, would block approval of competing drugs with more robust data packages, including Kyndrisa drisapersen from BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc.

The fact is that FDA could still approve Kyndrisa if BioMarin demonstrated superior safety or efficacy, or if the agency determined that the two products are not identical.

In January, BioMarin said FDA requested a new trial of Kyndrisa in a complete response letter. At the time, the company told BioCentury it would determine next steps after meeting with FDA and after a decision anticipated in June from EMA's CHMP on an MAA for the compound.

BioMarin submitted three placebo-controlled trials that enrolled 290 patients with the same subtype of DMD targeted by eteplirsen. The data showed Kyndrisa had a non-significant and modest numerical benefit on walking ability and did not demonstrate that drisapersen produced elevated dystrophin levels. Moreover, unlike Sarepta's small trial of eteplirsen, the Kyndrisa studies showed serious adverse events in patients who received the compound.

Send a signal

The eteplirsen approval decision will be an inflection point in the movement toward patient-led drug development and regulation. CDER's decision, and especially how it communicates it, will send a powerful signal to patients -- and to CDER staff -- about how seriously the center takes patient engagement.

FDA does not have an obligation to comply with the wishes of patients. But having asked them to engage in the regulatory process, the agency does have an obligation to explain how any decision it makes about eteplirsen is in the best interests of boys who have DMD today, and those who will learn they have DMD in the future.

Judged from this perspective, eteplirsen should receive accelerated approval.

Companies and Institutions Mentioned

BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc. (NASDAQ:BMRN), San Rafael, Calif.

European Medicines Agency (EMA), London, U.K.

Sarepta Therapeutics Inc. (NASDAQ:SRPT), Cambridge, Mass.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Silver Spring, Md.

References

Cukier-Meisner, E. "History lesson." BioCentury (2014)

Cukier-Meisner, E. "Patients lead the way." BioCentury (2015)

Cukier-Meisner, E. "Talking the walk." BioCentury (2015)

Figures

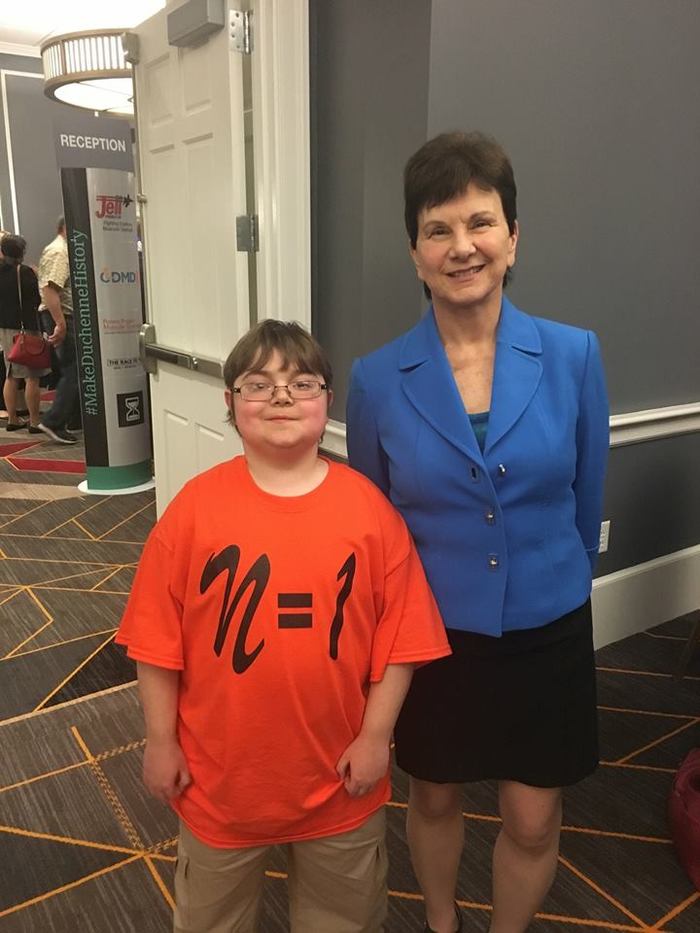

N = 1

Billy Ellsworth, one of the DMD patients who participated in the trial of Sarepta's eteplirsen, and CDER Director Janet Woodcock at the April 25 advisory committee meeting for eteplirsen, following his testimony to the committee. Source: Terri Wesley Ellsworth